|

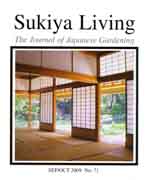

Shoji Screens

Curious about how to build a shoji door? Read this Article and learn more!

Some JOJG readers have mailed in questions such as "how do you make your own shoji screen." The following article was released as an introduction to the subject of shoji screens and how they are constructed. The article appeared in Issue #40 of Sukiya Living Magazine (JOJG) and included multiple photos and diagrams to illustrate various points in the article. It was published in July 2004.

One of the most common elements

seen in Japanese decor are sliding

doors with translucent white paper mounted on the outer side of a wooden

lattice. These doors are called shoji (pron. SHO-ji) in both Japanese and

English. Shoji doors require railing slots above and below the door. The

slotted beam above the door is called a kamoi beam, and the slotted rail

built into the floor is called the shikii (pron. SHE-key-ee). Shoji doors do

not have wheels under them, so they are carefully crafted to slide in their

slots using a one-finger push. It is the careful fitting and very smooth

finish of the wood that allows this.

Specialty Craftsmen

Shoji doors or windows are made by special craftsmen called tategu-ya. The

word tategu is a general name for the sliding doors and windows that serve

as wall openings in Japanese post & beam architecture. The word ya means

“roof” or “shop.” So the complete term, tategu-ya, means “workshop for

sliding doors” or the craftsman who works in that kind of shop. When

addressing the actual artisan you would call him a tateguya-san.

The sliding doors and windows in a Japanese house can be removed from their rails and stored in a hallway or adjacent room. Taking the doors out makes the room bigger, more open, and better integrated with other spaces such as the garden. The practice of removing the doors is common whenever a big room is needed for events like parties and funerals. If you live in a Japanese house, there is no need to be shy about removing the doors, but you have to be a little careful too. The doors are somewhat delicate and each of them is likely to be slightly different than the others. You need to remember the order in which they came out so they can be put back in the same order. Otherwise, you might find that some of the doors do not slide so easily.

Shoji paper is made of traditional paper called washi. Some casual gaijin

like to call it “rice paper,” but this is a myth. In fact, washi has nothing

to do with rice. It is made from fibers from a tree called kozo, which is in

the same family as the mulberry tree. The washi paper used for shoji screens is made

with a specific thinness that allows just the right amount of light to go

through. By changing the fiber direction and thickness, washi can control

two opposing optical factors such as reflection rate and transparency.

Shoji’s paper surface scatters sunlight evenly, making it soft to the eye

and allowing light to distribute evenly. This function of washi makes it

particularly suitable for indoor lighting fixtures such as Isamu Noguchi’s

famous “Akari” lamp shades. Even at night, shoji screens help light a room as

their white surface reflects indoor light and brightens the room. Shoji

paper is thus quite remarkable: it has no glare problem, maintains privacy,

and allows the light to enter in a pleasant way.

Function

Traditional Japanese homes have exterior shutters called ama-do. These

shutters are closed at night and during bad weather. Modern houses also have

glass windows. The windows can be installed directly in the walls as they

are in the West, or they can be floor-to-ceiling glass doors on the outboard

side of the engawa. It is important to note that a shoji screen, whenever it is used,

is positioned on the inboard side of the glass windows and wooden shutters.

Westerners are fond of installing shoji screens as shoji window blinds, but

in Japan shoji is usually positioned on the inboard side of the engawa

hallway, directly

between a tatami mat room and the engawa itself. On a nice day the home’s

shutters and glass windows might be opened up, making the shoji easily

visible from the outside. It’s important to note, however, that shoji doors

are not meant to be exposed to the rain or other elements.

Not only does it looks good, shoji has a practical side too. In tea houses that use charcoal, shoji screens have a distinct advantage over glass-covered windows or wooden doors. When air (gas molecules) move through shoji paper’s microporous structure, it leaves heat as the molecules bump into the fibers. Any outdoor air that filters into the room will receive heat as it comes in. The room feels warmer and at the same time the excess carbon mono/dioxides in the room can pass out and let oxygen into the room. Shoji is thus a motorless and soundless ventilator/heat exchanger. In Japan, there are some companies that apply this ventilation principle to kitchen and bathroom fan design, using washi paper in the heat exchanger section. Shoji paper is also known to help filter-out tobacco smoke and keep the adjacent room somewhat smoke free.

Culturally, shoji has been completely accepted throughout Japanese society.

Its natural materials, texture, color, lattice motif, and light quality are

all very familiar to Japanese people. It is a delight to see the moonlit

shadow of a nice pine branch on shoji doors at night. The songs of summer

and autumn insects can be heard through shoji. And the shoji-framed view of

a fresh snowfall is a classic scene in the Japanese mind.

Maintenance

Shoji can require regular maintenance, especially if you are rough on it, or

if you have no tateguya-san to turn to for repairs. The kumiko-lattice can

sometimes be broken, and the washi paper is so thin that a finger can poke a

hole through. Repairing this kind of minor damage is an annual task in many

households, and most people don’t mind doing it. After all, despite its

beloved role in defining space and primary views, shoji is not a structural

material, and most people understand this.

In fact, the graceful nature of shoji is a defining note of the Sukiya Living environment. Anyone can live in a steel bunker, using tin pans to eat from. But an aesthetically perceptive person wants more in life than just durability and practicality. After all, there are plenty of good people who are not ostentatious, but who still own silk garments or crystal-cut glassware that can’t be tossed in a dish washer. Why do they want such high-maintenance items? Because quality feels good, and it makes life feel delightful. Sukiya Living is all about quality, and quality requires maintenance. So changing the shoji paper every year or so isn’t such a bad thing.

The new paper will brighten up the room, and you’ll feel the satisfaction of completing a task. It’s the same way you feel after putting out clean bedding or a white table cloth. A small hole in the washi can be a chance to express yourself if you apply a small patch with a motif like a plum blossom. Because shoji screens require a gentle touch, people who live with them learn to move gracefully instead of slamming doors. Shoji is not sound-proof, but we learn not to talk so loud, caring more about others in the house. In case of secret talk, it’s best to open up all the doors and windows, just to make sure no one is around to hear.

A culture of delicate shoji doors does not give so much importance to what your job is or what kind of expensive things you own. It weighs more on what you did with what you got, and how well you can maintain the gracefulness of your surroundings and the quality of your life.