|

Garden Stepping Stones

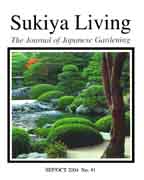

Some JOJG readers have mailed in questions such as "How do you position garden stepping stones?" The following article was released as an introduction to the subject of garden stepping stones. The article appeared in Issue #41 of Sukiya Living Magazine (JOJG) under the title "10 Hints for Better Tobi-ishi Paths." The article included multiple photos and diagrams to illustrate various points in the text. It was published in September 2004.

Stepping-stone paths should be easy to walk on. Despite

the overwhelming logic of this statement, myth-ridden

books and poorly-written brochures continue to imply that stepping stone

paths try to slow people down by being difficult to walk on or even

dangerous (see JOJG #28). Before attacking that stubborn myth, JOJG has

decided to outline some of the traits of good stepping stone paths - the

kind that are safe, beautiful, and a joy to experience. Here are 10 key

points for building high-quality tobi-ishi paths.

1. Simple, Logical Paths

Contrary to popular belief, the best JN garden paths take users from point

“A” to point “B” in a fairly logical manner. Paths need not be be

complicated mazes. It is better to be functional and beautiful. Of course,

this doesn’t mean that all paths should be straight and boring. The need to

change elevation, cross streams, and go around buildings, ponds, plants, and

boulders is already enough to make most paths very interesting.

To this add

beautiful surroundings and quality craftsmanship, and you have a delightful

journey.

The “standard” JN garden path runs from the house to an overlook stone (JOJG

#37). It is appropriate to make that kind of path more interesting by

arranging garden stepping stones in a slighty irregular pattern such as a zig-zag or

S-shaped curve. But don’t go too far. As someone walks along that zig-zag

path, their body should be able to proceed leisurely in the general

direction without any lunging, gut-sucking, or twisting.

2. High-quality Materials

As with everything else in Sukiya-style gardens, it is essential to start a

stepping-stone project with high-quality materials. The ideal material for

garden stepping stones is weather-worn granite. They should be flat and hard, with

a slightly rough texture to allow for traction. Polished stones are not

appropriate, because people will slip on them. Stones with angular corners

or irregular surfaces are not permitted because they create a tripping

hazard.

All of the stones in a given path should look like they came from the same

family, with similar texture and color. The ideal stepping stone is likely

to be gray or speckled gray in color. Some stones might have a blue tint or

patches of black. Avoid stones that are yellow, orange, red, and especially

muddy brown. While moss and lichen-covered garden stones are attractive, it

is inappropriate to use them as walking surfaces. Some people might imagine

that it looks quaint, but in fact it is hazardous and completely

inappropriate to allow slippery moss or any other plant to grow on stepping

stones.

3. Use SAFE Rocks

Do not use irregular, angular, sharp, cracked, or otherwise dangerous rocks

that can pose a tripping hazard. It doesn’t matter how large, flat, or

attractive the rock is. If it has any sharp corners at all it should be

rejected.

The edges of the walking surface are particularly important. They should be weather-worn and rounded to avoid snagging on heels or shoe soles. You must be concerned, not only with hazards that could cause someone to fall, but also with what they would fall ON if they did trip. The shoulders of garden stepping stones must be slightly rounded. It is also wise to avoid jagged or sharp rocks anywhere in the vicinity of the path, even if they aren’t part of the path itself.

Rocks that are perfect in every other way can sometimes be machined or

chiselled to smooth out the edges and corners. Likewise, a perfect rock can

be installed, only to become cracked or chipped and become a hazard.

Obviously, it would need to be removed or repaired.

4. Avoid Concave Stones

One type of stepping stone causes serious, hidden problems that are scary

enough to warrant special mention: the stone with a concave surface.

When initially installed, concave stepping stones are easy to walk on. In fact, they are actually comfortable because their shape allows you to feel settled into a stable positon. The problem is that same concave surface also causes mud and water to settle on the surface of the stone. At first the stone will just remain wet longer than the others. But after a few months or years, slime will develop in the concave area, and the stone will become slippery, even deadly.

The situation becomes even worse in the winter, when ice forms in the pool.

If a light snow then falls on top of the ice, you have the scary situation

of hidden ice smack in the middle of the very surface you aim for. Avoiding

these problems is simple. When building stepping stone paths, do not employ

any stone that has a concave walking surface.

5. 100% Wobble-free

It is a myth that garden stepping stones must be thin, coin-shaped slabs. True,

that’s how they appear on the surface, but it is quite common for stepping

stones to actually be much larger rocks buried in the ground, with only the

top flat surface exposed.

There’s a good reason for using rocks that are actually larger than the

coin-shaped slab that is exposed on the surface. Stepping stones must be

100% sturdy and wobble-free. It is a mistake to use rocks that are too small

or too thin. Such rocks inevitably shift, crack off, or become loose. Slate

and flagstone, for example, are easy to intall, but even when installed in

mortar it is just a matter of time before those thin slabs become broken or

loose. And a loose stepping stone is usually worse than no stepping stone at

all. The skilled garden builder will consider using chunkier rocks that are

sunk down in the ground. It requires more effort and more skill to set that

kind of “deep” tobi-ishi, but the added stability makes it worthwhile.

6. Employ Yaku-ishi

The word yaku-ishi means “functional stone.” These stones, in addition to

being handsome, have a specific role or purpose. Among other things, they

are used as steps, thresholds, and scenic overlooks (see JOJG #14).

Yaku-ishi are among the most important stones in any Sukiya-style garden.

At a minimum, each stepping-stone path should have large yaku-ishi positioned at the beginning and end of the path. If the path starts at the house, a kutsu-nugi-ishi, or “shoe removal stone,” should be the first stone at the house end of the path. If the path terminates at a spot for overlooking the garden, an “overlook stone” should be positioned at that end of the path.

Yaku-ishi can also be used at various points along a path. If a path

proceeds under a garden gate, a “threshold stone” can be positioned directly

under the gate. Large “junction stones” where paths merge are another type

of yaku-ishi. So are large garden stepping stones positioned at key spots to allow

people on the path to pass each other. If you want to have a stepping stone

path that is beautiful, charming, and entirely human in feel, the

incorporation of yaku-ishi is a key point.

7. Observe Stride Intervals

For comfortable walking, the stones of a tobi-ishi path need to be

positioned a certain distance apart from each other. The traditional stride

interval has been four stones for every 2 meters of path length.” This

averages out to be 50cm per stride, but it is best to use this as a guide

rather than a rigid rule. This is because stepping-stones are irregular in

size and because path layouts are so varied.

For example, extra-large stones can sometimes be used as “two foot” stones, whereby the user takes two steps on the same stone (see illustration). Another situation is the use of slightly smaller stones that are more difficult to walk on. They might need to be placed somewhat closer together.

Nowadays people are growing taller, and a slightly more ample stride

interval might be justified. For straight line paths using large stones, it

is reasonable to anticipate a stride interval of 55-60cm. The key is to

repeatedly “test walk” every path as it is being constructed. The actual

feel of a path is, of course, more important than textbook measurments.

8. Avoid Large Gaps

No matter how precise a path builder is, and no matter how carefully he

repeatedly walks along the newly-built path to check its “ease of

operation,” there are going to be a wide range of people using that path,

each with a different stride length and walking pattern. After all, a

person’s walking vigor change as she progresses through life. The child

takes small steps. She grows into an adult who takes long, vigorous strides.

Finally, as an elderly grandmother, she takes smaller steps again.

To compensate for these variables, it is appropriate to use fairly large

garden stepping stones with gaps of less than 10cm between them. The key to

avoiding large gaps is to place the stones so that edges of adjacent stones

are parallel to each other. This allows the garden builder to fit large

stepping stones very close to, and even directly against, each other. When

possible the gap should only be about 10cm wide.

9. Precise Elevation is Key

Garden stepping stones keep your feet up out of the wet weeds and mud. This is one

reason it is a pleasure to walk on them - you don’t need to tangle with

dirt, dust, and other unpleasant elements. But if the stones are too high

off the ground, they actually become hazardous. A stepping stone that is too

high becomes a mini-cliff to fall off. It becomes a spot were serious

injuries such as broken bones or concussions can occur.

Get it right. Stepping stones should be elevated 3-6 cm above the ground. If

you position tobi-ishi higher than this you create an unnecessary hazard.

Position them lower than 3cm and they will likely become covered with weeds

or dirt, making them slippery, messy, and difficult to see.

10. Be Level, Level, Level!

Stepping stones are a surface intended for leisurely walking. They are not

meant to be even the slightest bit challenging or dangerous. As a result,

stepping-stone paths must be perfectly level in two different ways: (1) Each

individual stone must be perfectly level, and (2) Adjacent stones must be

perfectly level with each other.

This point can not be emphasized enough. If you lay on your back on a well-done stepping stone path, it would almost feel like you were lying on the floor. Each and every stone would be perfectly level, without any angles or jutting protrusions whatsoever. In this respect, all good paths are the same; they may look varied from above, but when viewed from the side they are identical.

Public JN gardens in the West have a history of being negligent in

maintaining their stepping-stone paths. It stems from a general disregard

for maintenance. It also reflects an unwillingness to adjust or change what

a craftsman created long ago. Make no mistake about this: Of Course the

stones shift and need to be adjusted! Instead of posting “caution” signs, a

decent public garden should be adjusting its stepping stones each and every

year.

Conclusion

This article lists ten hints for building successful paths using garden

stepping stones. In addition to the ones listed, there are dozens of other important details

that we do not have space for in this article. Let it suffice to say that an

entire book could be written on the subject of tobi-ishi alone.

Creating beautiful stepping-stone paths is clearly a goal, especially when the path can be seen from inside the house (see photo, above). It is more important, however, to create paths that are ergonomically safe and a pleasure to walk on. After all, stepping-stone paths are first and foremost a walking surface. No truly skilled gardener in Japan would ever intentionally create a path that is difficult to walk on. Quite the opposite is true. If you want guests to be able to enjoy your beautiful garden, first give them safe and secure footing. Allow them the luxury of walking in a relaxed, leisurely fashion. Only then will they feel comfortable enough to lift up their heads and look around.